Every now and then, we receive feedback about our food that makes me pause, smile a little, and reflect on where we are — and what we offer. Over the years, we’ve been told our food is “not African enough.” More recently, we’ve been told it’s “not European enough.” And now, occasionally, that the dining room is not decorated enough. In many ways, that perfectly captures the unique space Malealea Lodge occupies.

The Recce Pony Trek in February 1991 By Caroline James

Caroline James shared this incredible story about a pioneering pony trek in Lesotho back in 1991. Sadly, in April 1998, she had a tragic skiing accident in the French Alps and passed away. She is deeply missed by all who knew her—her cheerful presence and wonderful sense of humor remain in our hearts.

More than three decades later, the incredible Malealea Pony Trekking experience is still available! The legacy of Simon Mokala, the legendary guide who led our pioneering trek in 1991, is now carried forward by his son, Nkhabane Mokala. With the same deep knowledge, skill, and love for the mountains, Nkhabane is the Pony Trek Association co-ordinater who organises the Malealea Pony Trek Guides to take visitor on unforgettable pony treks through Lesotho’s breathtaking landscapes.

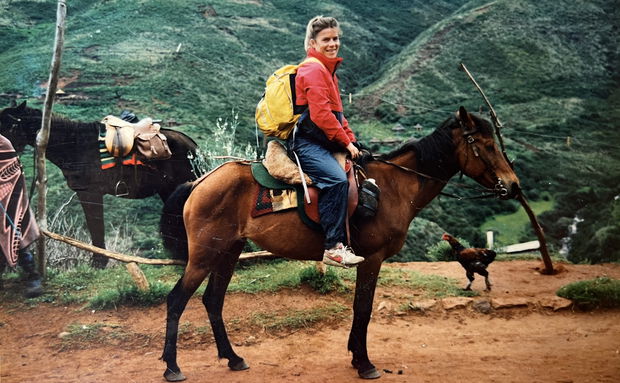

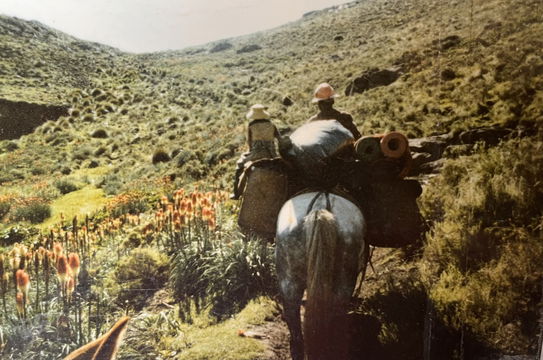

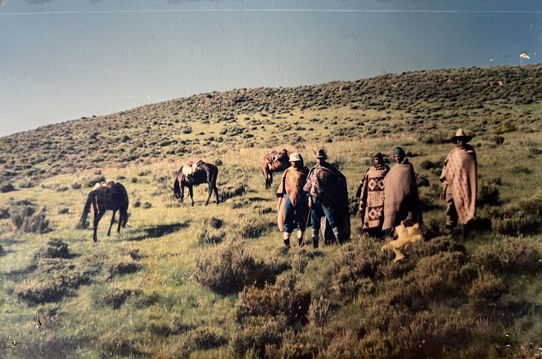

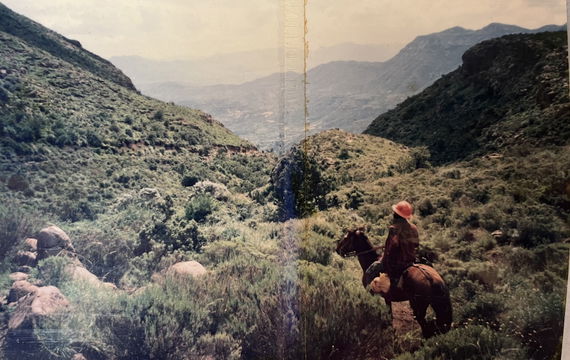

SETTING OFF FOR THE RECCE PONY TREK, WITH TSELISO MOKALA, February, 1991.

(The highest rainfall in years!)

“What kind of saddles did you say these were?” “Old South African army, I think, made for long distance riding”

she replied with a grin. “And the sheepskin covers are provided for extra comfort?” I asked wryly.

“Well, just imagine how you would feel without them”. We continued bouncing along the uneven ground in

companionable silence.

We live in a world of constant change, where development holds the key to the future. A frightening depletion of isolated wilderness and other rural areas, bear the testament to this progressive trend. There are still however, places where the passage of time moves in a slow more measured way, and life continues in a similar vein, regardless of events elsewhere.

Since my first visit to the mountain kingdom of Lesotho five years ago, there hae been noticeably few changes, even within the towns. In the villages a few new houses have sprung up amongst the traditional rondavels, but these apart, things remain the same. Development is minimal, there being too little money available for these projects. There are still aid programmes active within Lesotho . Many of these involve improving farming methods and teaching farmers about modern techniques, thus increasing production and output.

An independent country, the mountain kingdom of Lesotho has the unusual distinction of being completely surrounded by another – South Africa. It is a place of infinite beauty and rare contrasts, of towering mountains and lofty peaks, meandering rivers and mighty waterfalls, rolling valleys and shadowy ravines. Each season is well defined, and cloaked in its own colours; wavering plains of pink Cosmos, bright red summer Aloes, delicate spring peach blossoms, and winter white snow capped peaks. The country is home to the Basotho people a tough resilient tribe who are, for the most part, subsistence farmers. They graze their herds on the steep terrain and high passes, whilst planting their mealies on terraces cut out on the mountainside. It is a country whose lowest point of 1500 metres above sea level, is the highest in the world.

The history of Lesotho goes back millions of years, and yet the nation itself is very young. Before the Basotho arrived, the country was inhabited by Bushmen, whose many rock paintings have enabled subsequent visitors to understand and visualise their way of life.

In the early 1800s, peaceable communities of cattle owning people, who spoke dialects of Sesotho were scattered across the Transvaal highlands. During the 1820s, however, these Chiefdoms were disrupted by widespread Difaqane disturbances.

Between 1815-1829 Moshoeshoe the Great, possessing the intelligence and sensitivity to unite the fugitives of these wars, gathered the remnants of the tribes dispersed by Zulu and Matebele Raids, and created Basutoland withing the natural refuge created by the Maluti Mountain ranges in the west, and the Drakensberg in the east.

It was only in 1966, after a century of hostilities with its neighbours, that Basutoland gained independence from the British authority and became the Kingdom of Lesotho, ruled by King Moshoeshoe II – the third great grandson of Moshoeshoe the Great.

The mountainous topography of this country dictated that the horse become the universal form of transport. This led to the breeding of the traditional Basotho Pony which is descended from Javanese horses imported for their strength, sure footedness and calm temperament. They are called ponies because, as a result of their harsh environment, they grow no larger than a European riding pony.

Outside the major urban areas, electricity and telephones do not exist, and wild open spaces are paramount. Coming from Europe, where vast numbers of vehicles and people are cramped into increasingly small areas, and communication is taken completely for granted, this isolation has enormous appeal.

From the outset my attempts to organise pony trekking had been thwarted by bad weather and communication. At the time the only official pony trekking operation in Lesotho was the Basotho Pony Project. Establishes by the Lesotho government, this was initially funded and founded by the Irish Government to improve the breed of Basotho Pony. The aim of the scheme was to upgrade the pony trekking service and to make the industry as a whole more profitable.

I decided, therefore, to try Malealea Lodge in the Maluti mountains as an alternative. There, I had been told were plenty of hiking trails, and possibility of pony trekking. I met up with Mickey and Di Jones (the owners) and hitched a lift back from Maseru to the lodge with them.

The day I arrived had coincided with the end of the drought. The heavens opened and did not close for nearly a month. The skies darkened, great black clouds gathered, and the rain assaulted the parched land with unabated force. Mountain faces spawned networks of brown veins through which flowed a continual passage of water. Gurgling streams were transformed into rampaging, brown torrents, foaming and churning as they swept downstream, cutting deep swathes through the earth and bursting over their banks onto roads and tracks. Wonderful for farmer s, decidedly soggy and miserable for hikers, and impossible for pony trekkers – as I discovered – the pony owners would not set foot on the mountain with their animals, until the rains abated.

Malealea Lodge dates back to 1905 when it was establishes as a Trading Post by Mervyn Bosworth Smith. Educated at Oxford, this charismatic, colonial character fought in both the Anglo Boer and First World Wars. He fell in love with Basutoland and lived there for over 40 years. The small village at Malealea developed around the Trading Store, and since Mervyns’s death in 1950, the latter changed hands several times.

IN 1986 Mickey and Di Jones took over management of the trading complex, and in 1987 bought the property. Since them they have transformed Malealea into a fully operational and increasingly popular lodge.

Although not officially established, the requests for pony trekking from visitors to Malealea were increasing. There were plenty of pony owners in the village who were keen to take out more treks and a number of ponies to do so.

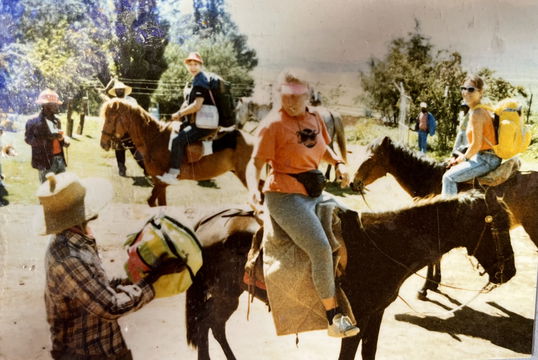

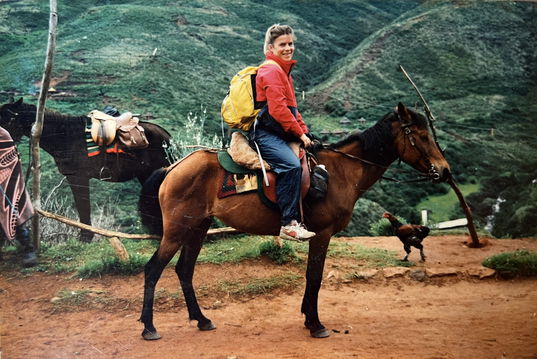

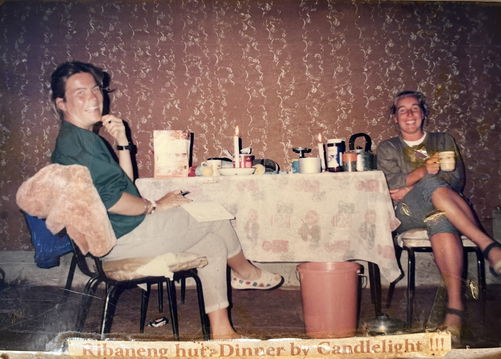

I explained that I wanted to go out for a few days, stay in local villages and explore some of the region in the traditional way, using ponies. Another girl also staying at the lodge was keen to do something along the same lines. Di suggested that the three of us go and do a test run, and see if something could be put together for future visitors. Mickey, on the other hand could not be persuaded nor bribed to accompany us, and so the Pioneering Malealea Pony Trek set out as an all female expedition.

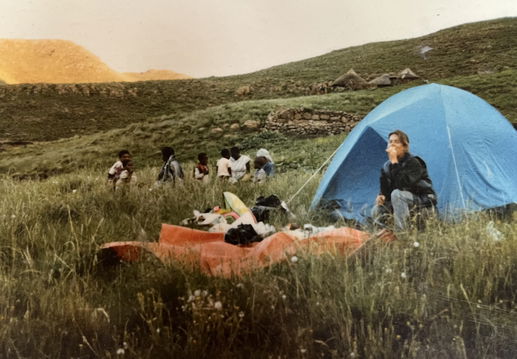

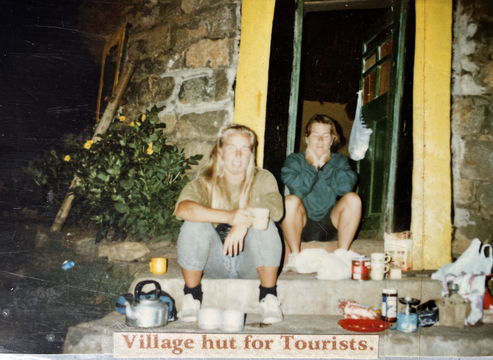

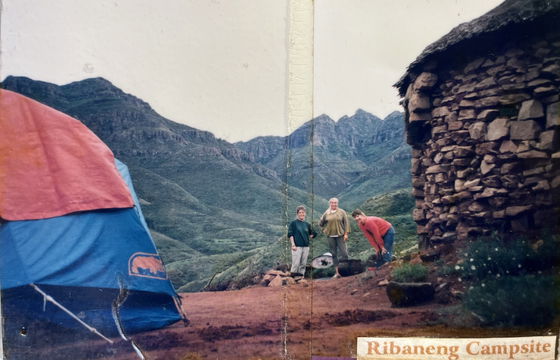

We decided, on this occasion to take a tent, and camp whenever necessary. At that stage no agreement had been established with the villagers for the allocation of specially equipped huts for trekkers. In due course, this would be the case, along with a long drop toilet. This would be done in exchange for every village receiving a commission for each visitor using the facilities.

This excellent eco tourism exchange has now been incorporated by Malealea into all pony treks and hiking routes.

The locals of Malealea have also established the Matelile Pony Owners Association, which acts as a pony trekking service for operations such as Malealea Lodge. Ponies are rented to visitors and the payment for each animal goes to its respective owner. An establishment such as Malealea, however receives a booking and commission fee. In this way the profits and well channelled.

To illustrate how the involvement of Malealea is helping overall, Di tells the tale of how one morning she went out to see a group of German clients off on a trek. Looking around at the ponies, she suddenly gasped in horror. There, saddled up and ready to go was a living skeleton. She rushed over and with the owner, led the horse away and out of sight of the visitors. She explained to the owner that overseas visitors came to Lesotho to ride the horses and learn about the country. When they go home to their own countries they tell their friends and others about their holiday and Lesotho. It would be terrible if they had o say that the ponies were starved and not properly cared for. The owner nodded his understanding and returned to the village mulling this over. Several weeks later his horse was again saddled up and ready for the trekkers – but, what a difference. It had picked up considerable weight and condition, and without one bone showing through its shining coat, looked alert and raring to go!

We put ourselves in the hands of the knowledgeable and extremely capable head guide, Simon Mokala. His only weakness, as we were to discover, was for a local liquid brew. Every now and then he would disappear off on some pretext or other.

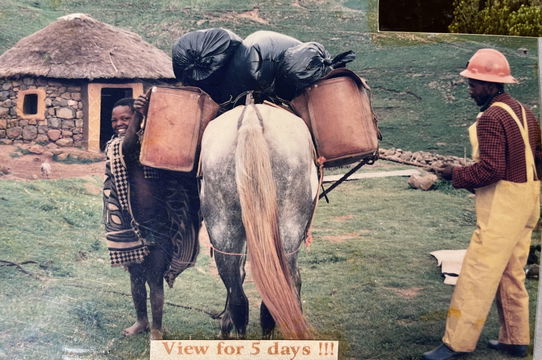

I woke to sighs of relief on the morning of our departure, – the day had dawned bright and clear. After a substantial breakfast, group photographs and a cheering farewell from Mickey, the Malealea Staff and half the village, we set off on our Great Trek through the Thaba Putsoa mountain range. Our trip was planned for abut 6 days, and would follow a route unused by Europeans for many years. Our ponies had been carefully chosen by Simon, as had the stocky grey packhorse – at that time almost completely concealed by two enormous saddlebags full of our equipment, and a lot of “not to be left behinds” that in hindsight, should have been.

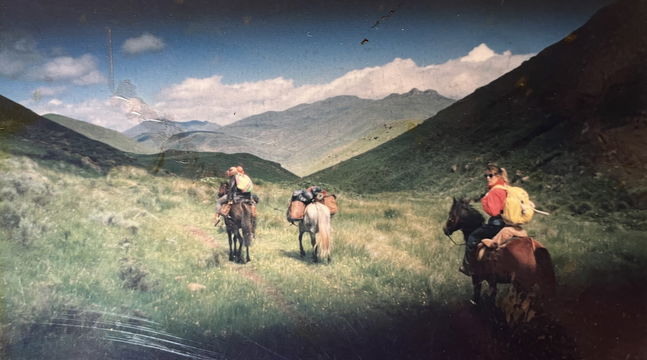

For the first time in days we had untrammelled views of the surrounding mountains. An uneven chain of ridges like jagged shards of sky, melted into penumbral escarpments, which tumbled into valleys of brilliant green velvet pleats. The landscape, washed clean of dust and grime by the recent rain lay before us in sharp clarity.

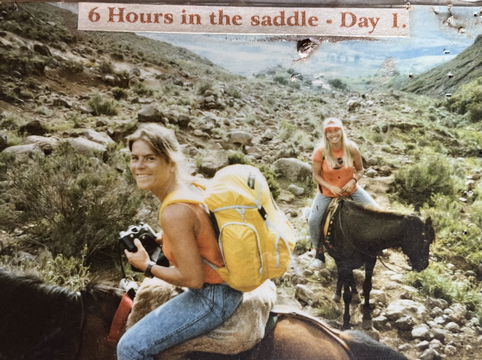

Not having ridden for years, we balanced precariously on our lofty mobile perches, straining muscles we hadn’t known existed. We set off from Malealea in eager anticipation as our ponies picked their sure footed way down a rocky, steep switchback trail to the river. This suicide track is used by motorbike competitors in the annual Roof of Africa rally, and watching them manoeuver down the sheer rock face has to be as nerve wracking as participating.

We were seldom on our own during the trek, and were often followed by groups of barefoot, raggedly attired children, whose liquid brown eyes gazed up at us beseechingly as they demanded sweets or money in strident tones. Just when we though ourselves alone in the wilderness , we would see scampering bodies materialise our of the mountainside and rush towards us.

Despite the short morning in the saddle, lunch the first day was a welcome break from purgatory. At the end of a steep climb, there was no feeling left in our behinds, and without exception we fell from the horses in sheer relief. It was decided then that it would make sense to walk beside the horses from time to time during the next few days. It would enable us all to stretch our limbs.

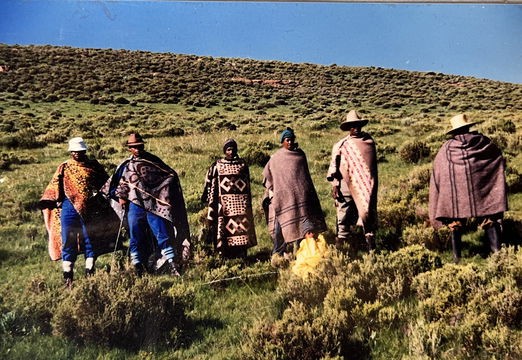

That afternoon, we climbed an impossible steep narrow, pass leading to Sekoting sa li Farike. We caused great derision amongst the local populace, as much by our presence on horseback, as by our intentions, related by Simon. We were joined on this ascent by a couple of well dressed and mounted Basothos, who asked us whether we were scared, so slowly were we climbing the mountain. I was surprised at the uncommon sight of a woman riding. She was dressed in trousers and high heeled shoes, a beret and had a heavy Basotho blanket wrapped around her. She was the only other horsewoman we were to see during our trek.

The terrain was precarious, steep and rocky, with stones that kept slipping from under the horses hooves. The ponies just took it in their stride and without altering their pace, picked their way to the tope of the pass. The valley fell away below us, a distant colourful patchwork of fields. We arrived at what had appeared to be the summit, only to discover another peak in front of us. Once over this, the path descended in a gentle curve around the mountain and down to the village where we were to spend our first night.

As Europeans we were a rare spectacle, and scrutinised as such. Simon had to ask the Chief’s permission for us to stay the night. Once granted we set about erecting Di’s 3 minute ZAR100.00 OK Bazaar tent away from the main village, but still the centre of attention for the gathering audience. The Chief sent us a cup of tea using his best enamel floral Tea Set.

Cosy for two, it was definitely overcrowded for three. With little room to manoevre, when any one of us wanted to turn over or leave the tent, it necessitated subtle group action. We also learnt about the porous qualities of our shelter, and that the bright orange groundsheet was of greater benefit above than below.

Wherever we stayed, we were of major spectator interest. We were rarely left alone, and although for the most part had no problem with the company, it became a painful ordeal trying to find an isolated spot for the morning ritual. By the end of the trek we had the ‘bunny hop’ practised to perfection. It entailed a rapid glance over the shoulder, followed by a series of smooth, fast tow legged hops, in any clear direction, with trousers affixed around the ankles. The trick was to avoid uneven ground and potholes!

The mountain telegraph never ceased to amaze us. A shout from one side of the mountain, would be answered by somebody on the other. This message would then be picked up by someone else and passed on to another. In this way the raucous calls would continue in an echoing chain across the ranges.

We learnt early on how little wood there was on the mountain, and certainly not enough for us to make a cooking fire each evening. As we had brought insufficient gas cylinders with us, (we also managed to waste away a whole gas cylinder in one go as we did not know how to use it correctly ) we ate very few hot meals, and largely depended on the villagers generosity for boiling water for drinks. We could not however , bring ourselves to expose our deluxe dehydrated Italian pastas to public analysis. We lived for the most part, therefore on biscuits, dried fruit and sandwiches.

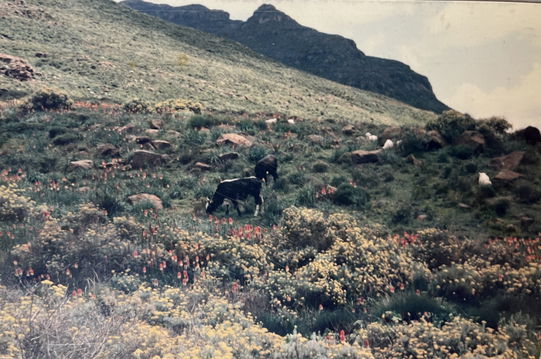

Feeling rather like the morning after the night before, somewhat battered and bruised, we struggled onto our ponies that second morning and eased ourselves gingerly into the saddle. The chief escorted us to the top of the mountain and after profuse thanks for his hospitality we set our for Ketane. The trails were in good condition which made the crossing of a number of high passes much easier. Throughout, we had spectacular views of the never ending sierras. Clumps of red hot pokers (flowering red aloes) dotted over the mountainside gave it a campfire effect. At one point we descended through a boggy mire into a valley of fiery licking flames. As far as the eye could see was a sea of waving red hot pokers.

The terrain was extraordinarily variable. We rode through gentle riverine vegetation, up steep rocky passes, across undulating plains, through meadows of alpine flowers, inhospitable marshy snow grass and moorland. Throughout, we came across small busy villages, full of chattering , curious people. “What is your name, where do you come from?”. How much they actually understood of our answers remained a mystery. Our second night was spent a the mission village of Ketane. Known for its magnificent 122m waterfall, the village sits at the edge of a deep gorge overlooking the distant layers of grey peaks and pinnacles. We were offered a rondavel by the Chief, but declined as we were becoming accustomed to life in a tent, and to the audience that seemed to go with it. We were quite tempted though at the thought of all the space provided by the rondavel. These round wattle residences are generally well built, with a thatch roof, and doors and windows. Being naturally well insulated they are cool in summer and warm in winter. Escorted by a group of eager children, and clutching our washing things and cameras we headed down to the waterfall. Our guides skipped down through the scrub, sheer rocky outcrops and faces with the agility of mountain goats. We, on the other hand slipped and stumbled, swung and panicked. The falls were magnificent, but not enough to keep us from the alluring clear blue waters of a nearby stream. | This was where modesty was cast aside asunder. From every vantage point on the surrounding mountainside, we were watched and ogled

at by blanketed Basothos.

We were lulled to sleep that night by the sounds of the night and village life, the whining dogs, baying donkeys, unsynchronised cock crows and imbibed villagers who stopped and prodded the tent in curiosity. The following morning we led the horses on foot our of Ketane and down to the river, which had to be crossed before climbing a steep pass.

Due to recent rains, the river had expanded in width, and the water was flowing fast and deep. We looked at one another anxiously. Simon found a suitable place to cross and led the way, but not that far. His horse was going nowhere, and leapt and reared and refused to listen to his commands. Simon dismounted and led the packhorse across in his gumboots. He left it on the other side and returned for his own horse, struggling on foot, against the strong current. He mounted his animal and plunged back across the river. We, in the meantime were having no joy with the horses who were rushing everywhere other than across the river. Sonia and Di went upstream and were last seen, holding their shoes delicately aloft with one hand, weaving across the rocks and through the flow, leading their horses to the other side with the other. They were, needless to say, soaked to the skin. I attempted to ride my horse into the river, but was nearly thrown in the ensuing disagreement. I them dismounted and started to lead it across. All would have been well had I not tripped over a rock and landed face down in the water. Still clutching the reins, I struggled to my feet and let the startled animal over to a rock where I remounted. We plunged into the deep water, and with the aid of a recently acquired switch, made it across the river – also soaked.

We climbed out of the river up a steep narrow path. The trail followed a narrow ledge around the cliffs with a sheer, long drop into the gorge on one side. It was extremely slippery and we kept a good distance between each pony. The way became so steep and precarious towards the top of the pass that we dismounted and led the horses. Immense relief was felt all round when we finally crossed over the top of the pass into undulating marshy grasslands.

The country opened up into great expanses of moorland where large herds of sheep grazed, and young herdboys in white gumboots and white miners helmets tended their animals.

We were often passed by proud horsemen wrapped in brightly coloured Basotho blankets and wearing sinister black Homburgs, during our trek. Astride their high stepping, arch necked mounts, these riders were reminiscent of their South American counterparts. They would always greet us and inspect our motley gathering, before galloping off into the distance.

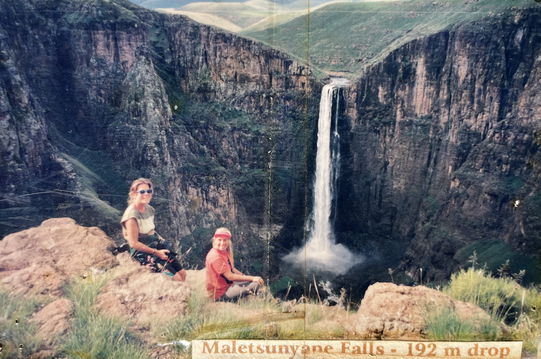

We saw the cliffs of the Lebihan Falls ( Maletsunyane Fall) on the Maletsunyane River some distance before we reached them, concealed at the end of a sloping grassy field. The falls are dramatic, as the water drops in one straight, powerful line from the top of the cliffs to the pool at the bottom. The falls are in fact the second highest in Southern Africa, but have the highest straight drop (192 metres) in Africa.

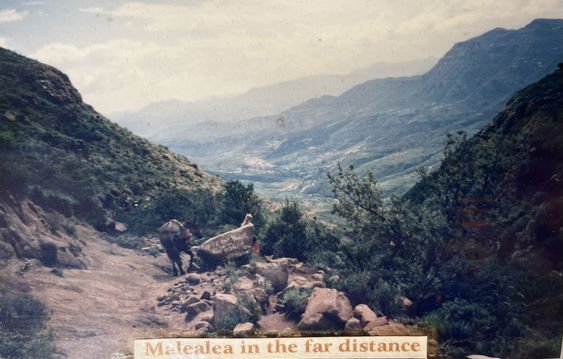

The falls marked the farthest point of our journey. From there we headed back in the direction on Ribaneng and Malealea. It was quite late in the day, and on remounting the horses we noticed the ominous low lying clouds, dark, threatening and pregnant with rain.

Within half an hour, the heavens had opened given vent to a torrential downpour. Before we managed to leap from our horses to put on waterproofs, we were saturated. The wind and rain drove head on as we trudged up the rapidly waterlogged, muddy mountainside. We should have been heading towards our night stop, but for some reason it was taking a very long time. We ode through village after village, by this stage absolutely freezing and soaked to the skin. Finally, after three hours in the pouring rain, and a long climb to the top of the mountains, we came to a halt in a small village.

This was one night where we would have been extremely grateful for the use of a warm rondavel. In fact, that very thought had been the one thing to keep us going during the long trudge in the rain. But, as luck would have it, that evening there was a meeting of local herdsman, and all the rondavels were occupied. We were allowed to leave our things in one of the huts overnight, but had to sleep outside. Fortunately, our sleeping bags had remained dry in their plastic garbage bag coverings. Our hands, however were so cold we couldn’t move our fingers which made erecting the tent an interesting exercise. Despite the roaring communal fire outside, the dry clothing and continual cups of hot coffee, we could not get warm. We eventually went to bed with one last longing look at the clean, warm cosy rondavel behind us.

The wind and rain raged around us all night, so much so that at one point the tarpaulin was ripped off the tent, and we had to stagger out into the night to retrieve it, and then tie the flapping object back on.

We headed out the following morning under blue grey skies, and scudding clouds. Simon was concerned that the trails might be too slippery and dangerous, but decided to take the chance. A meagre breakfast was eaten with the entire village in situ. These wonderful characters, farmers, herdsmen and their wives, all watched us with beaming faces. We departed for Ribaneng cheered on our way with great shouts and waves.

We climbed to the top of the mountain range, and rode into a biting wind. Views of the spectacular surrounding peaks managed, however to more than compensate for the discomfort.

We rode down through the most beautiful alpine meadows carpeted by a kaleidoscope of wild flowers. Our senses were invaded by the rainbow colours and pungent smells of wild lavender and herbs. Everywhere birds were swooping and gliding, Whydahs, Bishops, Widow s and others. We spent the day climbing and descending different mountain passes. Sometimes we rode, and sometimes we were happy to wander along leading the ponies. The final pass before the descent to Ribaneng was long and arduous. We struggled up the last part to the top and were rewarded by a remarkable downhill run. Scattered amongst the bush and rocks and bright red aloes, were herds of peacefully grazing cattle, goats and sheep.

The pass was so steep that once again we felt more comfortable leading the horses. The switchback trail wound its way down between the rock faces of the mountain. It is one of the routes in the Roof of Africa Rally and was aptly nicknamed, “Slide your arse pass”. At one point the riders abandon their motorbikes and just hurl them down the mountain.

The village of Ha Rasebetsane, near Ribaneng Waterfall, is situated near the lower part of the pass, protected from the elements. It is one of the best maintained villages in the region and the local Basotho have great respect for the privacy of visitors. It was extremely relaxing to be able to wander around and not have to play the Pied Piper.

We had a rondavel set aside for us and were happy to take advantage of this luxury, particularly as a storm lashed the village with full vitriol during the night. We left early the following morning and wound our way down the stony path to the valley below. We passed through wonderful orchards of wild peach trees, and treated ourselves to a second breakfast, eating the sweet, succulent fruits until we had stomach aches.

Once through the thriving village of Ribaneng we climbed a final stony pass before riding across the undulating valley, well on our way back to Malealea. We crossed the Makhaleng River, and once again found ourselves drenched by one of those fast and furious mountain storms. The rain eventually stopped, and we were able to climb the steep stony trail to Ha Phatela without too much concern. Then one final gentle stretch and we were at the gates to Malealea Lodge.

Had we really been away for 5 days. It seemed a lifetime, but what an experience, and what precious memories. We thanked Simon, and our horses and headed inside for a welcome cup of tea, and “how about a big bowl of steaming hot pasta”. There should be plenty left!!

- Caroline James

Further Reading

Dear Partners, It has come to our attention that visitors are stopping along the road to distribute sweets and biscuits to local children. While we understand this is done with good intentions, we must urgently ask that this practice stop immediately. Over many years, we have worked closely with community leaders and chiefs to discourage roadside begging. Unfortunately, these actions are undoing that progress and creating serious risks: Safety: Children are now...

🌄 A Note From Malealea Lodge — Updated for 2025 Where slow travel meets modern comforts in the Heart of Lesotho Since Marek wrote the beautiful story below about his stay at Malealea Lodge in February, 2025, a few things have changed here in the mountains — all for the better. ⭐ We’ve upgraded our entire internet system to Starlink, bringing: • Free Wi-Fi for all guests • Very high-speed connectivity —...

Share This Post